900 A.D.

Between the Waters

900 A.D.

To begin your tour of the historic grounds of Hobcaw Barony, click on the View Map button on this page. You will see a map of Hobcaw with hotspots that lead to places on the property.

Click on a hotspot, or on the “Explore” drop-down menu. Once you are in a location, use your mouse to “scroll” down a road or rice canal “walkthrough,” or to move around a panoramic view.

On the walkthroughs and panoramas you will encounter hotspots that lead to “popups,” “pages” and “jumps.”

The Hobcaw Barony story is made up of many stories. Take your time to discover them.

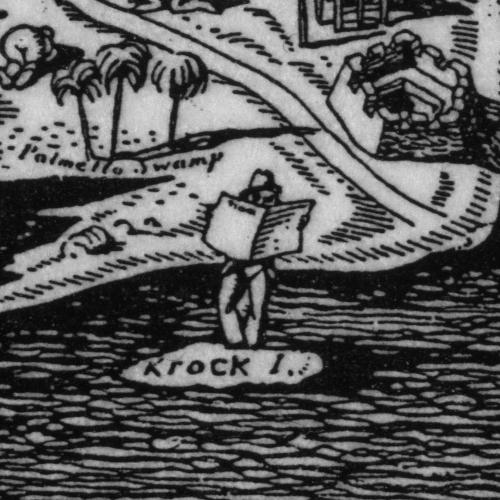

This map, Chart of Hobcaw Barony, by American artist Rockwell Kent, was created in 1927, after Kent visited Hobcaw as a guest of the Baruchs. The original pen and ink drawing hangs on the wall of the dining room of Hobcaw House, and more information about Kent’s life and work may be found in the pop-up there. Although Chart of Hobcaw Barony features outsize figures, trees, animals and buildings, it is fairly accurate geographically, and, of course, depicts a real place.

There are twelve human figures portrayed on the map. One of them, in the lower right corner, is a man reading a newspaper, standing on “Krock Is.,” the only fictional island on the chart. He is assumed to be the journalist Arthur Krock, who knew Baruch and published a flattering profile of him in the August, 1926 edition of The New Yorker. In 1927 Baruch set up a meeting between Krock and Adolf S. Ochs, publisher of the New York Times, and Krock subsequently joined the Times’ editorial board. In his memoir, Bernard Baruch mentions that Krock visited Hobcaw Barony almost every year.

A king-like character can be seen walking down the road leading to Krock Island, his robe held by two small, dark figures. Another figure kneels in front of him. This drawing could be a reference to the King’s Highway, which is roughly in that location, or it might be a satirical depiction of the “Baron of Hobcaw” himself - or both.

The fifth figure in the drawing, riding a horse not far from the king, is almost certainly meant to represent Belle Baruch. Another horse rides beside her, but the rider can’t be seen.

Near the bottom of the map is a man rowing a boat, heading for the boathouse at Little Dock, near the main dock at Hobcaw House. Before the construction of the bridge across Winyah Bay in 1935, the only access to Hobcaw from the south was by water. Although the Baruchs and their guests traveled in the family yacht, people of lesser means crossed this treacherous body of water in small rowboats. This poignant figure has been adapted as the logo for Between the Waters.

The remaining figures are located near the rice fields in the lower portion of the map. Standing next to two rows of small houses resembling Friendfield Village is a black woman surrounded by four tiny children, similar to the ones holding the robe of the king figure. She is a large, full- figured woman who appears to have a basket on her head. She can easily be seen as a classic mammy figure, a caricature of African-American women that is a painful and enduring racist stereotype.

In a September, 2015 article for The Huffington Post, reporter Julia Craven wrote:

The harmful influence of the mammy figure didn’t end with the abolition of slavery. The legacy of the idea stretched into the Jim Crow era, when black women often had to work as house servants if they wanted to work at all, and it still has currency today… Unskilled, undesirable, good-natured, simple-minded — these ideas about what black women are, or what they should be, have shaped social expectations for black women and made their opportunities smaller than they’d be otherwise.

By definition, the mammy is a subservient figure: someone defined by her relationship to whiteness, someone who’s perfectly happy being a second-class citizen.

The fact that Kent incorporated a mammy in his drawing raises difficult issues. Chart of Hobcaw Barony was created in 1927, during the height of Jim Crow, when this hurtful distortion of black womanhood was prevalent. The artist was a product of his privileged position and his era, creating a context for the inclusion of the figure. Although the context does not diminish the drawing’s potential for harm, ultimately this artifact is part of the complex history of Hobcaw Barony.